Analyzing the Effectiveness of Graziani vs Rommel

There is often a comparison between Marshal Rodolfo Graziani and Erwin Rommel during discussions of the North African campaign of World War Two. Marshal Graziani is cast as the personification of Italian ineffectiveness; the inability to achieve victory through a numerical superiority in men and equipment. However, Graziani and Rommel led two very different armies on the North Africa front, and in turn, their options were not the same. To compare the effectiveness of Graziani vs Rommel requires a much deeper look.

In debating Graziani vs Rommel, It is important to understand the different circumstances under which Graziani and Rommel lead their forces.

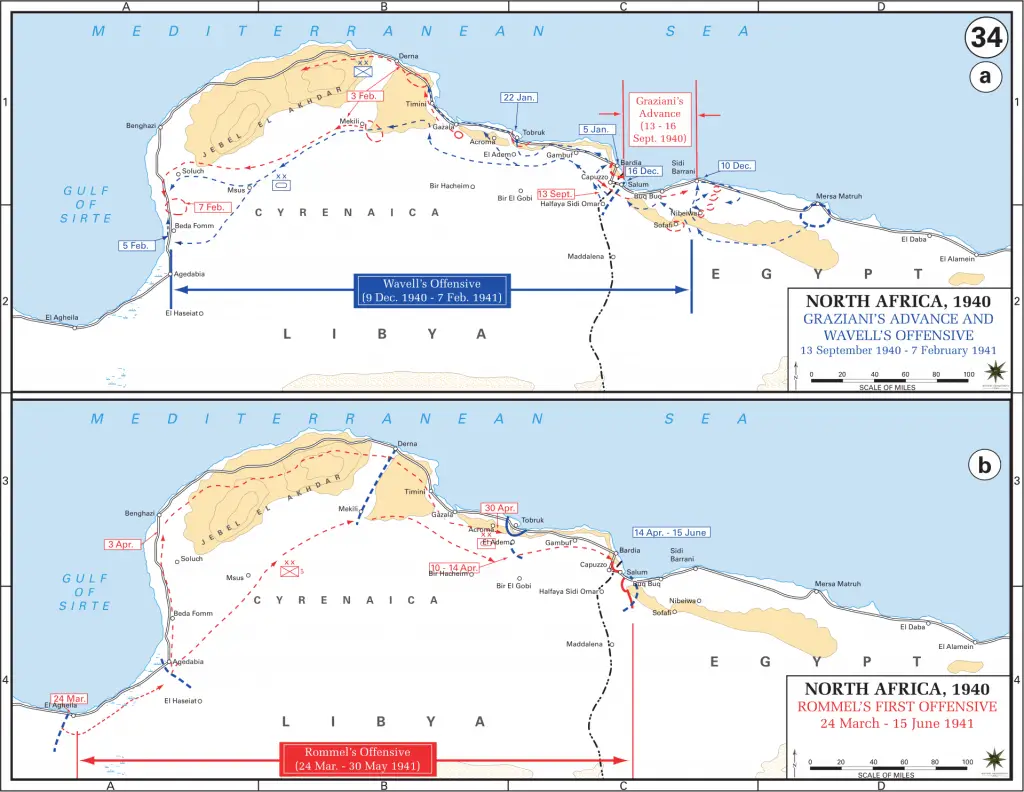

On 13 September 1940, Graziani began his advance into Egypt with seven Italian and Libyan divisions. They met little resistance from Wavell’s forces and eventually pushed forward to Sidi Barrani, approximately 60 miles inside the Egyptian border.

Strength of Graziani and Wavell’s Forces

Prior to the invasion, the difference between Graziani and General Sir Archibald Wavell’s forces must be studied. Graziani had under his command the following force:

Troops: 236,000 encompassing 14 divisions (28,000 of which were native troops). These troops made up the 5th Army in the west and 10th army in the east.

- Guns: 1,500 (elderly and obsolete)

- Tanks: 300 (obsolete)

- Aircraft: 300

- Trucks: 8,000

Against the 10th Army faced the British forces which amounted to:

- Troops: 50,000 (86,000 spread throughout Wavell’s command)

- Aircraft: 205

The most mobile of these British forces was the 7th armored division, which consisted of 300 armored cars, light and cruiser tanks, as well as many Bren gun carriers.

Denied Requests for Motorized Transport and Armor

Initially, British forces utilized limited attacks inside Libya, which caused the Italians to reinforce the 10th army through the 5th army, transferring 2,500 vehicles and receiving 70 M11/39 tanks shipped from Italy prior to Graziani’s invasion.

Once Graziani’s forces reached Sidi Barrani, he set up defenses facing east and south. He used this fortification because he realized the limits of his supplies. He asked Mussolini for additional motorized transport, as well as tanks. Telegrams exchanged back and forth between Graziani and Mussolini. Mussolini answered Graziani’s requests with orders to continue the invasion and occupy Alexandria. Graziani understood his troops and limited motorized forces could not achieve this goal. What we now know is that Mussolini was actually saving a majority of available weapons for the planned invasion of Yugoslavia.

Pietro Badoglio eventually promised to ship 1,000 tanks to North Africa, but Graziani knew this would not occur. In fact, Italy produced fewer tanks throughout the war than Germany used against France in 1940.

Graziani’s request for armored divisions was based on the 1938 manual which required “M” tanks as the core of each unit for penetration effect, “P” tanks as mobile artillery (the P.40 was the most advanced Italian tank developed, but never utilized), and “L” tanks as scouts. Graziani was forced to use the “M” and “L” tanks for all three.

Wavell Strengthens His Forces

As Graziani negotiated, Wavell reinforced his forces with 31,000 troops, 120 guns, and 275 tanks; among which were 50 Matildas and 100 Cruisers, 60 armored cars, and 150 aircraft. Some of these new aircraft were Hurricanes, which outclassed any Italian aircraft in the region.

Italy Loses Ground

By mid-February 1941, a majority of Graziani’s forces are overrun and 115,000 men surrender. Wavell’s forces destroy 845 Italian guns and 380 light and medium tanks. The British manage to destroy 200 of the 564 Italian aircraft.

The British on the other hand lost 80% of their vehicles, all their “I’ tanks and most of their light and cruiser tanks. British casualties amounted to 2,000 troops. One in 25 troops who engaged the Italians died. The British were also, at this point, suffering the same logistical problems Graziani faced.

Enter General Rommel and Deutsches Africa Korps

During this same period, General Erwin Rommel arrived in Tripoli, Libya. He arrived with a Panzer and Motorized Infantry Division to assist the ailing Italian forces. Rommel assumed command of the Deutsches Africa Korps and received assistance from the Fliegerkorps X and long-range aircraft from Sicily to fight the British. The German 5th Light Division included 9,300 Germans, 130 tanks, 111 guns, 2,000 vehicles, as well as 80 German aircraft.

Should All Credit Go To Rommel?

The success of Rommel’s Africa Korps is well known and publicized. But the reason why is usually limited to adjectives such as his “genius”, or “great tactician”. This article is not to discredit Rommel, but can one man really make all that difference? How did Rommel achieve results that Graziani could not manage?

Although German assistance played a factor, the evolution of the Italian forces in the theater also helped the Italo-German forces to achieve their successes in North Africa between 1941-1942.

A map showing Graziani’s gain and losses and Rommel’s first offensive gains.

Credit To Increased Italian Armor

When Rommel arrived with a Panzer and Motorized Infantry Division in February 1941, The Italian “Ariete” and “Trento” Divisions arrived as well from Italy. The “Ariete” comprised of 6,949 men, 163 tanks, 36 field guns, 61 anti-tank guns, and the Brescia Infantry Division. Rommel had at his disposition 100,000 Italians, 7,000 Italian trucks supplying munitions to the front, 1,000 Italian guns, and 151 Italian aircraft. The Ariete began to use the 90/53 anti-aircraft guns capable of piercing 100 mm of armor at 1,000 yards. But this firepower is only slightly greater than the number of forces Graziani had at his disposal during the beginning of the North African offensive. So this cannot be the entire explanation.

It was, in fact, something completely different. After January 1941, the Italians introduced the more modern M13/40 tanks, grouped in motorized units and not thrown together as in the initial offensive. They also utilized their first company of armored cars with RECAM (Reparto Esplorante di Corpo d’Armata di Manovra). By early 1942, each armored division nominally had 47 armored reconnaissance cars and each motorized division had a battalion of M13/40’s.

Also in early 1942, the “M” tank chassis was incorporated with the 75/18 mm howitzer, which fired armor-piercing and high explosive shells that could penetrate most British armor. To erase the poor performance of some obsolete artillery, the Italians were the first to use these Self-Propelled Guns in close support and in anti-tank attacks by “massing” the artillery. Italian forces favored the rear guard artillery, rather than the German preferred “direct fire”. This maximized the effectiveness of the Italian weapons.

The Italian army was still not very mobile, but they now packed a much more powerful punch.

Credit to Increase in Italian Artillery

These methods of attack and improvisation could not be done in 1940 with what Graziani had available. In 1940, the Italian forces in North Africa had a 6:1 ratio of artillery to infantry battalions. The British had 8:1 The British had seventy-five 25 pdrs per division, an Italian division had twenty-four 75 mm and twelve 100 mm guns. By the end of 1941, the Italians doubled the amount of 100/17 mm guns to 24, and added 12 88/55’s or 90/53’s, giving each Italian division a total of 60 guns for a ratio of 10:1. This almost doubled the amount of firepower available for Rommel which was not available to Graziani’s forces in the initial invasion.

Same Problems Surface

In the end, however, Rommel suffered the same problems as Graziani, lack of armored transport, supplies, and a reinforced enemy.

Source Material

“Of Myths and Men: Rommel and the Italians in North Africa 1940-1942” by James J. Sadkovich.

“The North African Campaign 1940-1943: A Reconsideration”. By Lucio Ceva